Who Reads Malay Manuscripts? The Impact of the Bollinger Digitisation Project at the British Library

24 abril 2024

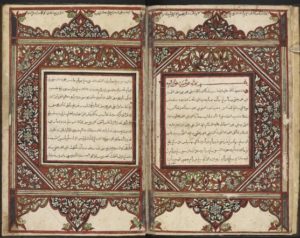

The British Library holds a small but important collection of about 120 manuscripts written in the Malay language and the Jawi (Arabic) script, originating from all over maritime Southeast Asia. These Malay manuscripts have always – in theory – been accessible publicly in the reading rooms initially of the British Museum and the India Office Library, and latterly in the British Library, but in practice access was restricted to those who could afford to travel the long distance to London. Microfilm was the standard reprographic medium at this time, which could at least enable manuscripts to be shared, but only the most dedicated philological scholars were able to tackle the cumbersome microfilm readers. In the 21st century, digitisation has been a game changer: now anyone, anywhere, can read a centuries-old Malay manuscript, on a computer at home, or on their smartphone while waiting for a bus.

Through the generous support of William and Judith Bollinger, over a two-year period from 2013 to 2015, the British Library was able to digitise its complete collection of Malay manuscripts in a collaborative project with the National Library Board of Singapore. The digitised manuscripts can now be accessed freely and fully online, both through the British Library’s Digitised Manuscripts portal and on the National Library of Singapore’s BookSG site. A full list of the 120 digitised manuscripts can be found on the British Library’s Asian and African studies blog.

However, in the crowded digital universe, it was also important to find effective ways of bringing this valuable resource to the attention of audiences in Southeast Asia. Fuelled by a conviction that all manuscripts have a unique story to tell, each Malay manuscript was given its Warholian ‘15 minutes of fame’ through the British Library’s Asian and African blog. The blog posts, which were further promoted through Facebook, gained a faithful audience, and by 2020 Malaysia and Indonesia were the two top countries for readers of the BL Asian and African blog after the UK, US and India. Outlined below are some innovative uses of the manuscripts we have heard about.

The digitised Malay manuscripts are now in constant use by scholars all over the world for teaching and research. Each year, Asep Yudha Wirajaya, a lecturer at Universitas Sebelas Maret (University of the Eleventh of March) in Surakarta, Central Java, sets his philology students to work on a digitised Malay manuscript from the British Library, including those accessible through the Endangered Archives Programme, and I frequently receive emails directly from Pak Asep’s students inquiring about particular manuscripts. It is rewarding to see tangible outcomes from these classes, and the Hikayat Selindung Delima (BL MSS Malay C.6) – containing the only known prose (hikayat) version of a tale more commonly found in poetic (syair) form – was published in 2019 by the National Library of Indonesia, edited by Dita Eka Pratiwi under the guidance of Asep Yudha Wirajaya.

Many of the Malay literary manuscripts in the British Library were collected by John Leyden (1775-1811), who spent several months convalescing in Penang in 1806 in the house of Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781-1826). The Malay poem Syair Jaran Tamasa (BL MSS Malay B 9) appears to have caught Leyden’s attention, for in one of his notebooks he had begun an English translation. In a blog I noted that to this day the Malay poem is unpublished, with no other manuscript known. This ‘challenge’ was picked up by Dr Mulaika Hijjas at SOAS, who devised the innovative ‘Jawi Transcription Project’ to crowd-source the romanised transliteration of this manuscript.

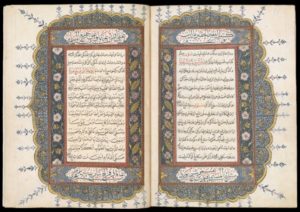

The involvement of the Malaysian ‘indie’ publisher Fixi is particularly gratifying in extending the reach of Malay manuscripts beyond a traditional scholarly audience and bringing alive these centuries-old tales for a modern audience. Two British Library Malay manuscripts have already been published by Fixi in appealing bibliographical formats, both edited by Arsyad Mokhtar. With its many fight sequences, Hikayat Raja Babi, ‘The Story of the Pig King’ (2015), has been designed to appeal to silat or kung fu aficionados, with comic manga-style illustrations. On the other hand, the hardcover Hikayat Nabi Yusuf, ‘The Story of the Prophet Joseph’ (2018), is a deluxe production on glossy paper with a sumptuous palette in keeping with the setting of the story in Pharaonic Egypt, with decorated frames inspired by another British Library Malay manuscript, Taj al-Salatin. Recently, ‘The Malay Tale of the Pig King’ (2019) has also been issued by Fixi as a children’s book in English, retold by Heide Shamsuddin with illustrations by Evi Shelvia.

Many of the manuscripts were celebrated in the National Library of Singapore’s exhibition Tales of the Malay World in 2017 and in the accompanying book, which featured 14 manuscripts from the British Library.

We look forward to seeing more creative and innovative uses of the British Library’s digitised Malay manuscripts, now that they are openly and freely accessible all over the world.

Written by: Annabel Teh Gallop, Head, Southeast Asia Section, British library