Libraries as Literacy Champions: an Indonesian Case Study

07 September 2022

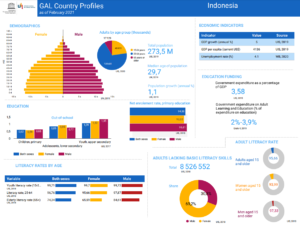

To mark International Literacy Day 2022, we’re taking a look at the work done by libraries in Indonesia in order to help the over 8.5 million people lacking basic literacy skills there to develop the capacities they need to participate fully in the knowledge society.

Indonesia is the world’s fourth biggest country in terms of population, and covers a vast area of land and sea, with over 17 500 islands, of which 6000 are inhabited. It is a middle income country, with a GDP of nearly 5000USD per capita, still some way short of the global average of over 12 000USD.

The country has made important strides in delivering on goals around schooling and literacy, with net enrolment rates of nearly 95% overall (although this is higher for boys than for girls), and an adult literacy rate of over 95% (although again, with a gender divide in favour of men).

Nonetheless, in a country the size of Indonesia, even a small percentage of the population represents a large absolute number of people. Over 8.5 million adult Indonesians lack basic literacy skills, and more still will lack more advanced abilities, with over 2/3 of this number being women – see the UNESCO factsheet for more.

As a result, Indonesia is a member of the Global Alliance for Literacy, organised by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, created to advance the drive towards zero adult illiteracy globally.

As a result, Indonesia is a member of the Global Alliance for Literacy, organised by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, created to advance the drive towards zero adult illiteracy globally.

Indonesia’s libraries have placed the fight to ensure universal literacy at the heart of their work. Hardly a photo is taken of a library event without people making an L-sign with their fingers to symbolise literasi (literacy in Bahasa Indonesia). This case study looks at the structures in place to support this work, the philosophy behind it, and the initiatives carried out.

Structures for supporting literacy

As highlighted above, Indonesia is a huge and complex country, with over 160 000 libraries across the country. Many of these are school libraries (around 82%), but there is an infrastructure of 34 provincial libraries, and 514 district libraries, as well as over 3000 university libraries.

Furthermore, there is a comprehensive library law (Law #43 of 2007) which, in particular gives a strong role to the National Library of Indonesia (NLI) in Jakarta in the development of libraries and library services across the country. Significantly, the law places the NLI directly under the President of Indonesia, giving important possibilities to engage with other parts of government without having to go through a parent ministry.

In addition to activities around supporting library associations, developing standards, gathering and publishing indicators and impact stories, the NLI has a leading role in literacy

A comprehensive approach to literacy

The work of the Indonesian library field on literacy is a consequence of a conscious drive to place libraries at the heart of social justice and inclusion efforts, aimed in particular at helping people in poverty to realise their potential and enjoy their rights. This also sits closely with the theme chosen for Indonesia’s G20 Presidency – Recover Together, Recover Stronger.

A key point is the recognition that efforts cannot stop only at basic literacy, but rather extend to other forms of literacy that enable fuller participation in economic, social, cultural and civic life. Digital literacy is an obvious example, but a wider ‘knowledge justice’ agenda also focuses on enabling people to be creative and put their skills to work.

A further aspect is that of building partnerships and mobilising activists. There is a recognition that libraries cannot do everything, but rather can make critical contributions to the work of others in order to achieve success. In particular, libraries work to train and support literacy champions who come from the communities they are serving, and so can have maximum reach and impact.

Connected with this is an emphasis on local culture and knowledge. Literacy efforts should combine with this, both in order to maximise their own effectiveness, but also to elevate communities and their culture. Though this, it becomes possible to draw on local wisdom in order to promote productivity and development, and help people to become citizens of the world.

Literacy promotion at work

To put this all into practice, the NLI has set up the Literacy Academy (Akademi Literasi) which brings together activists, materials, and success stories in order to inform, support and celebrate work across the country. Through this, the goal is to create an ecosystem not just of libraries, but also of other organisations and committed partners.

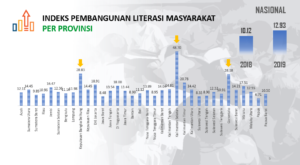

Through this, anyone interested in literacy can not only look at analysis of performance across regions – including data from Indonesia’s literacy development index – but also find out about and sign up to be a supporter library or literacy activist. In the case of the latter in particular, there are examples of the people championing literacy in their areas, including celebrated authors. The site has a particular focus on digital literacy, with competitions on the topic and winners celebrated.

Through this, anyone interested in literacy can not only look at analysis of performance across regions – including data from Indonesia’s literacy development index – but also find out about and sign up to be a supporter library or literacy activist. In the case of the latter in particular, there are examples of the people championing literacy in their areas, including celebrated authors. The site has a particular focus on digital literacy, with competitions on the topic and winners celebrated.

Crucially, and as was highlighted in our story about events in Indonesia involving IFLA earlier this week, and about the Urban 20 meeting, much of this work is taking place through partnerships.

To give one example, that of Rodinatun, a woman from Bekasi near Jakarta, was particularly strong. Having used library resources to develop a business selling craft made from plastic waste, she has become a literacy champion in her area, helping housewives like her realise their potential.

Similarly, Nirwan Ahmad Arsuka presented the Pustaka Bergerak – or mobile library – movement, which worked closely with the NLI in order to fill gaps in provision, and deliver access to materials that would otherwise be missing, as well as doing things in a culturally appropriate way. His initiative has received international recognition, and will be presented at the Istanbul Biennial later this year.

There are many other such examples across the country, providing evidence of how libraries, working with local authorities and with the support of the NLI are delivering positive outcomes on the ground.

The example of Indonesia is potentially a powerful one for the Global Alliance on Literacy, overcoming significant challenges around distance and logistics in order to deliver in a comprehensive way. It is also interesting as evidence of successful collaboration, not just horizontally (between actors on the ground), but also vertically (between levels of government, with the National Library at the top).